China Adapts to More Sustainable and Culturally Relevant Skyscrapers

In October of last year, the Chinese government announced a ban on supertall skyscrapers—ones that would be taller than 980 feet. Even buildings significantly smaller are also now “strictly restricted.” As a result, architecture firms have had to adjust their approach, turning to sustainability and cultural relevance. [The global standard definition for supertalls is 980 feet, though in China the term is sometimes applied to buildings 230 feet and above.] And the new regulations and sensibilities are leading to a fresh wave of architectural innovation.

“While China ranks top in terms of total number and annual growth rate of supertall buildings, issues such as costs, energy consumption, safety, and environmental impact have become an increasing concern,” said deputy minister of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) Yan Huang after the announcement of the ban.

Over the last decade, urban growth and high prices for land in major Chinese cities have contributed to a frenzy of construction supertall skyscraper developments. According to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) (see pages 26-27), 56 of the 106 buildings taller than 660 feet that were built in 2020 were in China—and China (the world’s most populous country) is home to 2,581 buildings that are over 490 feet tall, including 861 above 660 feet and 99 above 980 feet.

Skyscrapers like the Shanghai World Financial Centre (left), the Shanghai Jinmao Tower (middle), and the Shanghai Tower (right) would not likely be approved under the new restrictions

Recently, China’s love affair with supertalls has come under strain following more than a few half-finished buildings, empty towers, and environmental and safety concerns. According to CTBUH, as of September 2020 there were 81 unfinished skyscrapers in China where construction had been suspended— and 66 of those are expected to never be completed.

So (in October of 2021) MOHURD and the Ministry of Emergency Management issued a joint notice about “strengthening the planning and construction management of supertall high-rise buildings.” It stipulated that the development of supertall buildings over 1,640 feet must stop nationwide and that cities with populations of less than three million must also restrict the construction of high-rise buildings of more than 490 feet and ban those above 820 feet outright.

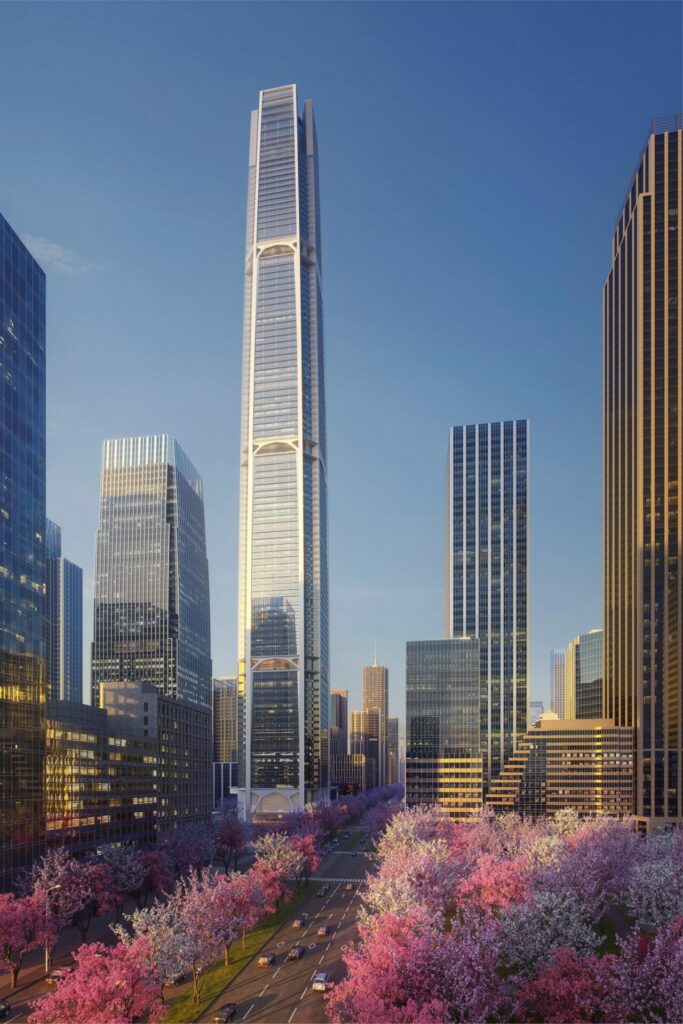

Many ongoing projects were forced to revise their original designs. Others have been allowed to continue; for example, Nanjing Greenland Jinmao International Financial Centre, (Picture 2) designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) is currently under construction and set to become the tallest building in Jiangsu Province with a height of 1,640 feet.

The building uses structural arches which SOM said were based upon the curved gateways of Nanjing’s ancient city walls.

More sustainably designed skyscrapers like the WeBank headquarters (which is nearing completion) in Shenzhen (Picture 3) (also designed by SOM) are starting to emerge in the wake of China’s announcement of a roadmap to see carbon emissions peak before 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2060.

The building will have a network of atriums that act like breathing lungs for the building’s large, mezzanine-style floors. (Picture 4)

“Architecture plays a vital role in reducing carbon emissions, and architects must incorporate that mindset into their design process,” said Bryant Lu, vice chairman of Hong Kong-based studio RLP, the firm behind the 720 foot-tall office building ‘Treehouse’ in Hong Kong, (Picture 5) which provides self-shading inclined facades on the upper floors.

Vertical forests – towers with facades covered in plants – have been gaining popularity in high-rise design over the past decade thanks to their energy-saving capacity for helping to regulate building temperatures. Italian studio Carlo Ratti Associati has released plans to build a 715 foot-tall (51-story) skyscraper in Shenzhen (Picture 6) that will dedicate 107,600 square feet to the cultivation of crops, creating a vertical hydroponic farm.

It is expected to produce 270 tons of food per year, (enough to feed roughly 40,000 people), creating a self-sustained food supply

Some architectural firms are finding other ways to make sure their high-rise projects appeal to the authorities. China’s General Office of the State Council, for example, signaled its desire to see transit-oriented development (TOD), which puts large construction projects together with railway improvements.

Hong Kong based Ronald LU and Partners (RLP) is particularly interested in TOD and has used it to win support for a project well above the 820-foot “strictly restricted” threshold. Wuhan CTF Financial Centre. (Picture 7) Currently under construction, it is one of the latest examples of urban TOD in China. It is comprised of a 1,560-foot–tall office building, two residential towers, and other commercial complexes, all connecting two urban rail transit lines.

China’s attraction to skyscrapers is unlikely to go away, particularly since, when done well, they represent the pinnacle of both architecture and engineering of this era. Shape and form will, of course, remain of paramount concern, but the incorporation of history and culture into the design will play a bigger role.