by Angela O’Byrne, FAIA

Nearly three years ago, the world watched in stunned disbelief as Notre-Dame de Paris burned. To watch one of the world’s most iconic landmarks engulfed in flames was a surreal reminder that nothing can be permanent or certain, no matter how central it is to our collective imagination.

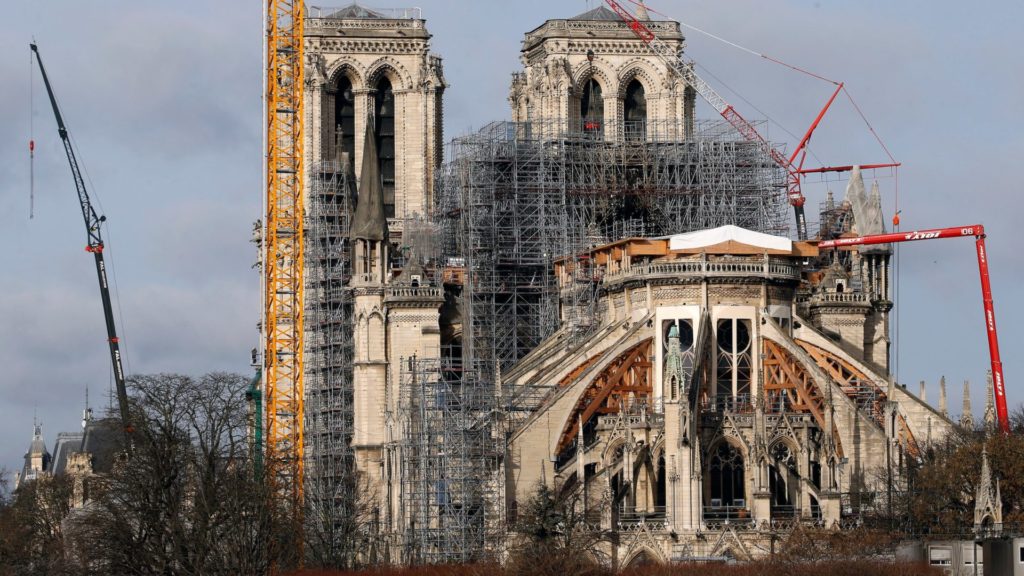

After fifteen hours of firefighting, the blaze was finally extinguished. While the fire damaged the lead and oak-beam roof extensively and destroyed the building’s flèche (a spire towering above the nave), much of the building—including its two towers and its breathtaking stained-glass windows—survived. Almost immediately after the fire, conversation turned to swiftly rebuilding and restoring the landmark. And it didn’t take long for that conversation to turn into a spirited argument.

Over the course of 850 years, Notre Dame de Paris has often been the object of dispute, a crown jewel constantly changing hands, shifting meanings, and reflecting the moments that make up France’s turbulent history.

Sitting on a site that’s believed to have once been a Roman temple to Jupiter, the cathedral has been renovated, expanded, and re-contextualized so many times since that a short history is impossible. The cathedral held the relics of the Passion of the Christ, including the crown of thorns said to have sat on Jesus’s head. During the French Revolution, Notre-Dame was desecrated, stripped for precious metals, and converted into a Temple of Reason. Soon after, the cathedral hosted the coronation of Napoleon. Later in the 19th century, Victor Hugo wrote The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in an act of architectural advocacy, raising awareness of the building’s neglect and decay leading to a restoration effort that would cement Notre-Dame as a national symbol. By the 21st century, it was the most visited monument in Paris.

It’s no wonder, then, that emotions ran high in the immediate aftermath of the 2019 fire. When the French government announced an international design competition to design a roof and spire “more beautiful than before,” backlash was swift and strong. The wounds of the fire still fresh, there was little appetite for contemporary reimagining, and soon French president Emmanuel Macron backtracked, vowing that the restoration would be “exact” and completed in time for the 2024 Olympics in Paris. Thanks to Covid-related delays, Macron’s timeline may need a series of miracles.

Logistically, the restoration will need to go to elaborate lengths to match the cathedral’s condition pre-fire. In 2021, a national search was conducted to source the 1,000 oak trees required to reconstruct the “forest” of wooden roof beams that fueled the fire. Crews scoured forests throughout France—sometimes by drone—for trees 150 years and older. The effort drew considerable opposition from ecological groups who objected to the harvesting of such old growth stock.

Concerns about potentially-dangerous fallout from the building’s incinerated lead roof also linger, especially among the neighborhoods around the cathedral. France’s aggressive timeline for restoration could put workers at risk, as testing of the site has shown lead levels hundreds of times higher than the safe threshold. And yet, the restoration’s plan calls for a continued use of the toxic metal for the roof and spire. Perhaps ironically, the spire in question dated back only to the 19th century restoration, when Eugène Viollet-le-Duc recreated the weakened medieval-era flèche.

More recently, alarmist scrutiny has turned against proposed updates to Notre-Dame’s interior, drawing fire in a larger, ongoing culture war. Those who see “traditional” French history and iconography as under threat have begun to panic about a “woke” and modernizing restoration to Notre-Dame. Intended to invite wider audiences into conversation with the divine, the additions include more open space, digital projections of welcome, and the incorporation of contemporary art.

Objections to the updates may have more to do with freezing Notre-Dame in time than the intent of the cathedral. The building’s many sculptures were intended to offer a “liber pauperum” or a “book of the poor,” illustrating biblical stories for illiterate visitors. Multilingual digital projections may serve a similarly inclusive purpose.

No matter how it’s done, Notre-Dame’s restoration is bound to incur the wrath of some concerned party. And if Notre-Dame reflects our times, maybe it’s fitting that its current incarnation is that of the subject of virulent debate.